IEC: Greetings and welcome Nasser.

Nasser Mohajer: I'm very happy to be with you and hope I can contribute a little to your understanding of what is going on in Iran which is not being covered as it should be in European and North American journals and newspapers.

IEC: Recently, Iranian officials have spoken about the necessity and possibility of repeating the massacre of 1988.[1] Let me quote the Fars News Agency, which is very close to the security apparatus of the Iranian regime:

Why should we not repeat the experience and the executions of 1988? Don't you think that the time for repeating that successful experience is right now? That we should repeat the experience that helped us to run the country for so many years without any problem and we didn't have to deal with the problem of terrorism and now after you know this terrible war and aggression towards Iran we can feel safe if we get rid of our enemies the exact same way that we got rid of them in 1988.

This is what they put out on the 8th of July, 2025. What do you think will happen with this threat?

NM: We still don't know. What we know is that in the last few weeks they have announced that some 2,000 people were arrested and jailed…. We have witnessed executions every 2 or 3 days. [They are] making a state of siege situation in big cities…. the number of Afghans who were arrested—some two million of them—migrants who were expelled from Iran in one of the most inhumane acts that one can think of, just expelling people who were living there and had made a life for themselves in Iran, who had worked and lived honestly and been very helpful to society… at least six of them were [executed] last week due to their [alleged] service to [Israel’s] Mossad…. It is difficult, of course, to go find the big shots among the leadership of the Iranian government, to say that they are agents of Mossad, the Israeli secret police. But it's easy to find poor Afghan people and say that they were collecting information for Mossad.

This is one of the dirty tactics they have been using in the last few months. All of this is to make an atmosphere of fear, intimidation in a society where it is already in a very turbulent kind of a mood because of the war that came so suddenly. People are still asking themselves, how did this happen, where are we going, and is it going to happen again? Are they going to continue the war or not? It’s a situation that is just questions and wondering about the future of everything.

IEC: How much do you think students, or those in the Iranian diaspora or people worldwide know about the 1988 massacre? Right now, prisoners all across Iran are participating in the weekly “No to Execution Tuesdays” hunger strike. But to this point, that has not become a mass movement in Iran, nor are people all over the world paying attention. What was kept secret in 1988 is now being openly called for by the regime. So what is going on?

NM: That is a very good question. How they executed those political prisoners, how they were tried in Middle-Ages kind of courts—or I’d better say so-called courts—because they were not really courts in the modern sense of the word as we know it…. nobody knows [about] how those political prisoners were tried.

We know that 5,000 to 6,000 political prisoners were executed in that summer. But people know very little, if anything at all, that they were tried in kangaroo courts with just a few questions such as “do you believe in God?”; “do you pray?”; “do you believe in the organizations that you were working with?” If the answers were [no, no and yes] to these questions, then they were hanged. The details of this are not known. It was kept as a state secret. They never talked about it in their newspapers or magazines….

People outside of Iran in the Diaspora know more about what went on, if simply because many political prisoners who were released after that experience came to Europe and North America…. People write their memoirs about what happened.

We're living in a very different situation from 1988…. I think we have to see these differences, but we all should also be ready to see some new tactics, some new so-called innovations on the [IRI’s] part for this round. How it will happen, the particular form that it will take is very difficult for me to predict…. We have to be very cautious and we have to be very alert. We have to talk about this. It is important to make people sensitive to this possibility. It's very much possible to happen. And, the more people know about such a possibility, the better it is.

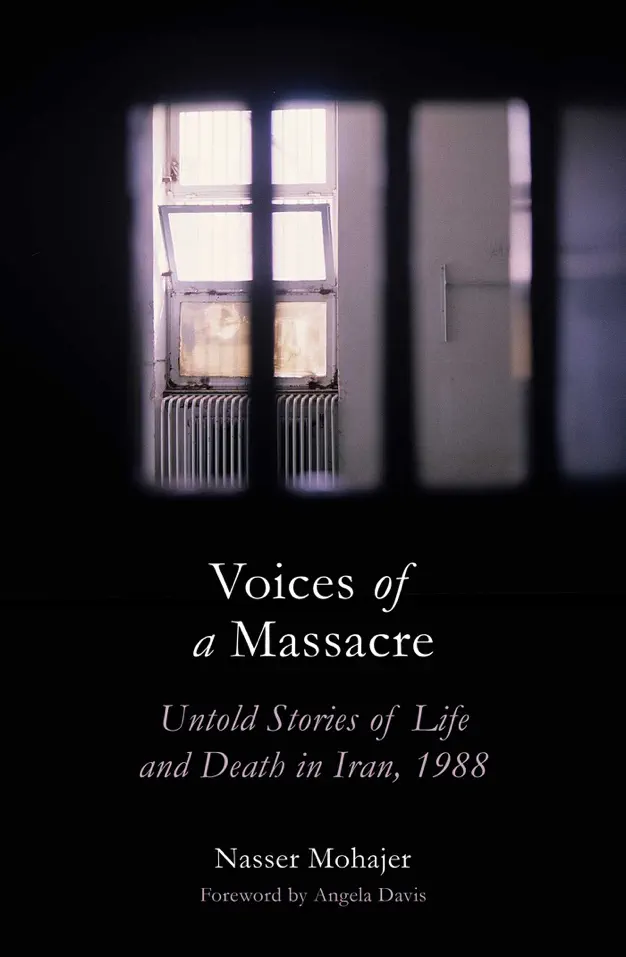

IEC: That was very important. Today, with social media, there are different ways to get out this understanding, for people to be alerted. One thing I love is that you are very concerned about accuracy and getting the facts correct. Most significantly, your book talks about the hopes and dreams of those who survived, and relatives and loved ones of those who we lost in that massacre.

The title of one story in your book is “He held his head up.” The imagery has great meaning for Iran’s political prisoners today—showing no fear and standing up. I read a letter from Golrokh Iraee, who is in Gharchak prison right now. She put in the poetry of Nâzım Hikmet “until their last breath, ‘I know that they smiled all the way, staring at the enemy. They did not bow down.’” It’s something people need to know—the heroism of the political prisoners, what they are fighting for—a different world that [many of us] would like to get to. Your book brings out the humanity of those loved ones, the culture of resistance, of people being proud of what they had done [in resisting].

NM: That started before the Iranian revolution of 1979[2], and during the 10-15 years before that. A new attitude had developed among political activists. It would take a book to talk about the culture that developed at that time. An important element of that culture was that it is important to fight. It is important not to bow down. It is important not to just go along. If we are people who believe a certain thing, we are going to keep to it. We have made an identity for ourselves and no one can break this identity. We can go to jail, and even after being beaten savagely by henchmen in prison, political prisoners are not going to say, ok we accept your words, we will be good boys and good girls and go along with whatever you tell us. No!

Something happened back then, seeing prison as another front of struggle—going to prison does not mean the struggle is finished. Going to prison means that a new stage in the struggle for our democratic rights has started. And each place requires its own ways and means of struggle. In prison, we are political prisoners, and as political prisoners we have certain rights. This is happening in the “No to Execution Tuesdays.” For over a year, every Tuesday, people in 50 prisons in Iran, and even outside of Iran, there are acts in solidarity with the prisoners, they go on hunger strike.

Some 60 years ago, before the Iranian revolution, the struggle going on inside Iranian jails was [mass] struggle, and civil disobedience. Iranian jails were called universities of revolution. They would read books. Many books were not allowed—simple books, novels that were considered illegal by the Shah’s regime. Books with leftist tendencies were considered illegal. Many newspapers and magazines that were free all over the world were considered illegal in the Iran of the Shah’s regime.

So for these very basic rights, they had to fight, they had to say, “You say we cannot have books? We cannot buy books from bookstores outside? We somehow smuggled books into jail, and we do reading here.” We learn things, and we understand what is going on in the world—what was going on in Vietnam at the time, what was going on in the U.S., in the 1968 movement and everything.

I think this background will help to understand what is going on right now in jail and why, even in this very difficult period, especially after the Israeli military forces bombarded the notorious Evin prison, we see many very courageous reports of exactly what happened during those days in Evin prison. For the first time, we have live reports of something that happened last night, two nights ago. In 2 days, 24 hours, we have detailed reports from different prisoners in different parts of Evin prison, explaining what happened, how it happened, how the regime officers and henchmen were treating them during those very difficult days and nights.

IEC: This courage of the political prisoners is so significant—especially the women prisoners who have really shined.

NM: The Islamic regime of Iran is one of the most misogynistic regimes that one can find in the world. And this happened even before the [1979] revolution. When you had great rallies, great demonstrations, the religious fanatics would come and attack the lines of demonstrators and threaten women who were not properly dressed—meaning they did not have the Islamic hijab—tell them to have their hijab or to leave the demonstration. So at events before the revolution, one could see small signs of the future. They would hide this when talking to the international press, [by saying] men and women are going to have equal rights, we are not going to impose anything on women, women are objects in capitalist society and we are going to give them their real identity, and so forth. That was the propaganda. But in reality something else was happening. The first demonstration against the Islamic Republic of Iran was 8th of March, 1979, right after the revolution. People came to the streets and said, we do not want to wear the hijab [in order] to go outside or work at a job, okay? And from then on we see every two or three years, another act by women, led by women against the regime.

So what happened is that the Islamic regime of Iran came to discipline women in Iran and put them in their place, meaning housekeeping, child rearing, cooking in the kitchen. The opposite happened. Iranian women saw themselves in a life-and-death struggle: if we do not move, if we do not fight, if we do not resist, we are going to have a very bad future. I mean it is apartheid, a kind of a system where women have little rights. The Women, Life, Freedom movement really changed the situation to a great degree.

The history of women prisoners in Iran is very much like the 45 years of struggle of women outside of the prisons in Iran. Each time we saw women more militant, women more vehement, more intelligent in their work and in their demands. And now one can easily say that women are playing the most active role inside the Islamic Republic’s jails.

So that is one important thing about understanding the role of Iranian women at this time, and trying to understand why women are so active in all walks of life, in all realms in the society. I think it was with women that the term “victim” was somehow banished inside the jails. “What do you mean I'm a victim? I'm not a victim. I have decided my own life. I know what I'm doing. I act as the subject. I'm not an object. I'm not a victim. I don't want to be a victim.” Many discussions like that with profound philosophical meaning.

IEC: Could you speak to this question of “never again,” and how that should become contagious? What can we do for “never again” to become “never again for anybody,” not just in Iran, not just in prison, not just U.S., but all over the world?

NM: This “Never again” is now an international thing—and then you look at Israel! To say really never again, if we want to have something not happen again, we must work for it. We must educate people, go to school, we have books that we are reading. We have films that we have to watch. We have teachers who come to our class and talk. If you want to get rid of this situation that we're living in, and if never again is going to be never again, it really takes work, hard work, and foremost, education. Of course, it cannot be reduced to education or limited to education….

We are human beings. We need to have certain rights. We need to live in dignity. We need to live in equality. We need to have a better future… society organized in a different way and educated in a different way, frankly. I remember very clearly the civil rights movement in the ’60s, and the achievements of that movement in terms of bringing a little more equality between men and women. That is being threatened by the political establishment right now. I think that the most important thing is re-education, reorganization of the system and to be able to look at things from a different angle and live in a different way than we have been living.

IEC: There is an event that is going to happen in early September in Europe commemorating the massacre of the 1988. Can you to speak to that?

NM: Thank you very much for bringing out this question. I think the most important thing at the moment is solidarity with political prisoners in Iran. Any campaign for solidarity: sending messages, having programs discussing the real situation in Iran, in the Middle East. The Middle East is going through a very difficult, crucial time. We are living in a very bad world…. There must be a movement of solidarity much [broader] than [among] the Iranian political prisoners or political activists or people who are not with the Islamic Republic of Iran. And now we can say with certainty that the vast majority of the Iranian people do not support and do not identify themselves with the Islamic Republic of Iran.… We do not know what is going to happen in few months’ time. Society is going through a lot of changes. There is so much discussion amongst the different wings of the Iranian regime. We do not know what will happen to this internal fight that is going on there.

Even though the Iranian society is in a weak, crucial moment of its life, I think solidarity with the people of Gaza is much more important. It's a shame of humanity. When I watch the TV and look at these kids dying every day, 50 of them, 60 of them, I mean this cannot be tolerated. History will make judgment on our generation as it did judgment on the generations of the late 1930s and ’40s in Europe. I think more than anything else there is the importance of solidarity with the people of Palestine in Gaza. That's my last word.